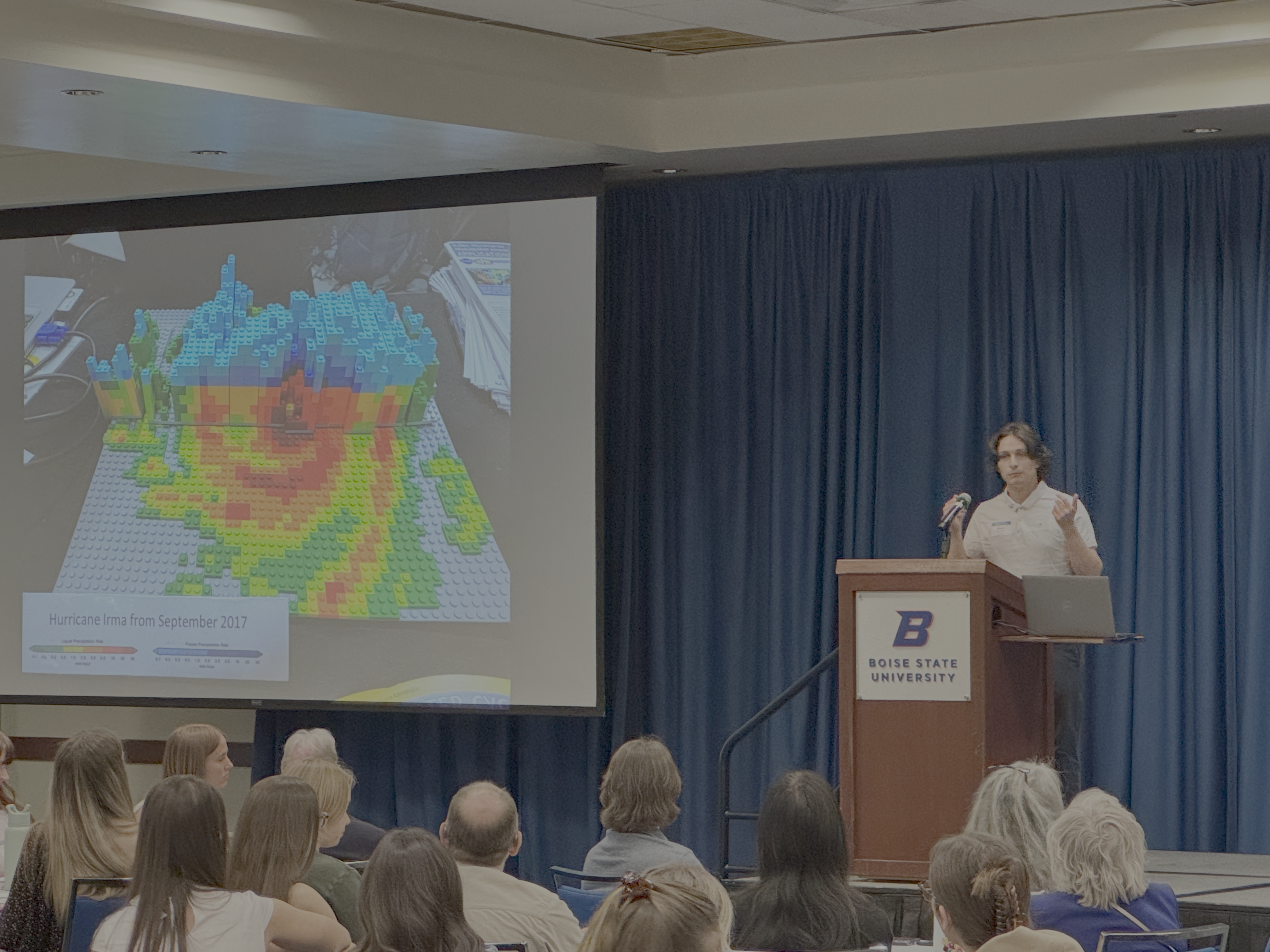

Last week, I had the privilege of presenting my research on Numerical Modeling of the Ocean to a remarkable audience: the Systemic Access, Blind Math, Blind Computer Science, and Blind Science and Engineering group of the National Federation of the Blind. This was no ordinary talk, as it challenged me to rethink how to communicate complex scientific concepts to a visually impaired audience. Typically, my presentations rely heavily on animations and visual graphs—tools inaccessible to this audience.

Faced with this challenge, I collaborated with Amelia Palmer-Dusenbury, an MS student in Mathematics, to develop innovative solutions. Together, we explored two main strategies to convey our findings: 3D printing select visualizations and sonifying key results.

Bringing Ocean Flow to Life Through Sonification and 3D Printing

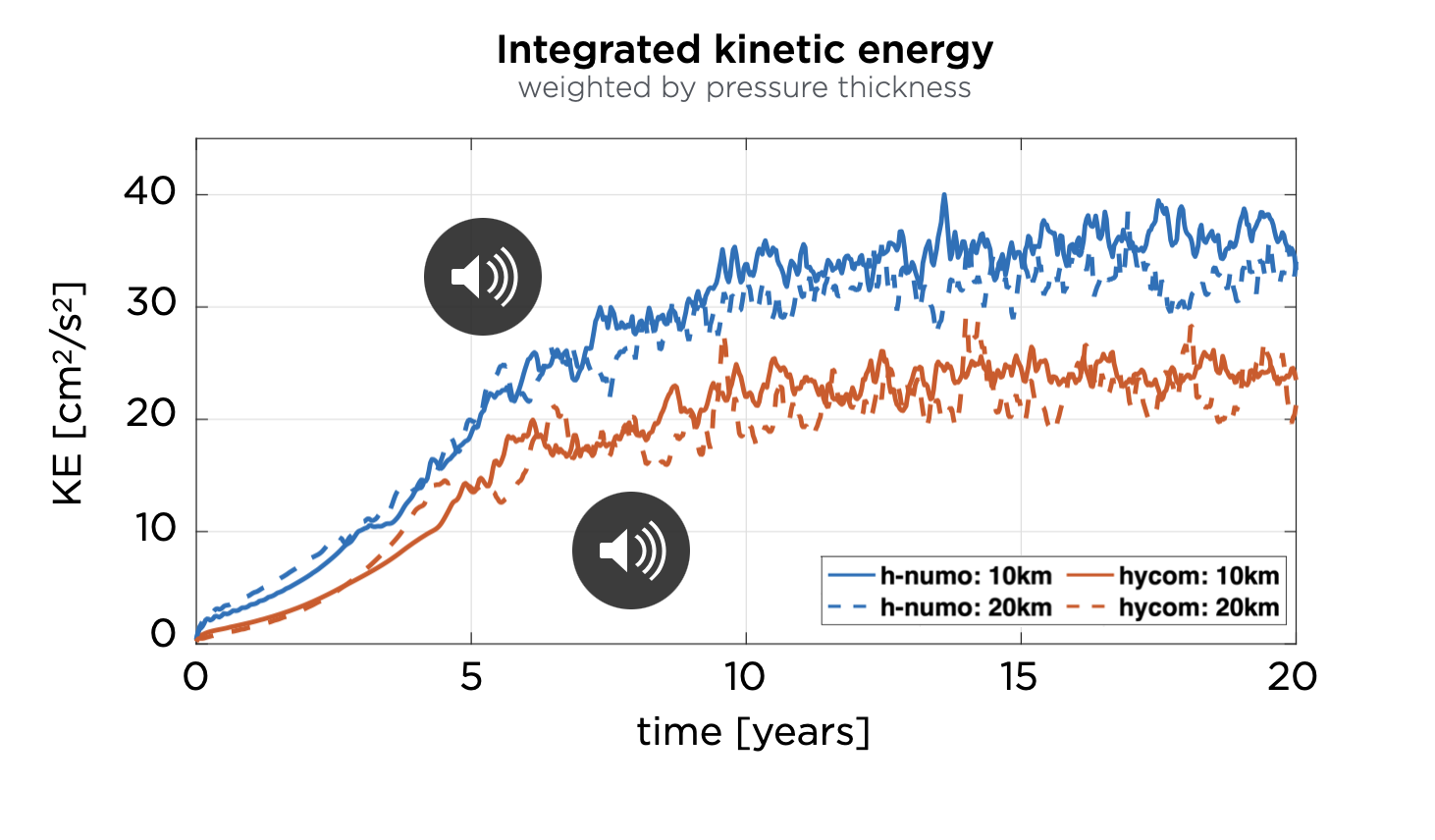

One of the main topics of the talk revolved around a double-gyre ocean flow simulation, comparing results from the HYCOM model and the h-NUMO prototype. Amelia and I experimented with 3D printing plots to offer a tactile way to represent features like sea surface height and streamline patterns. This was more challenging than I expected, as a seemingly simple conversion of a surface plot to an .stl file does not necessarily result in a 3D-printable model. However, the real breakthrough came with sonification: translating numerical data into sound.

During the talk, I shared sonified time-history data of the averaged kinetic energy from our simulations. Listening to these sonified results allowed the audience to hear the differences between the models. For instance, participants noted that h-NUMO calculated consistently higher levels of kinetic energy compared to HYCOM. The engagement was incredible. By using sound, we enabled the audience to interact with the data in meaningful ways, fostering a discussion as nuanced as those at any research conference.

Reflections on Accessibility in Science

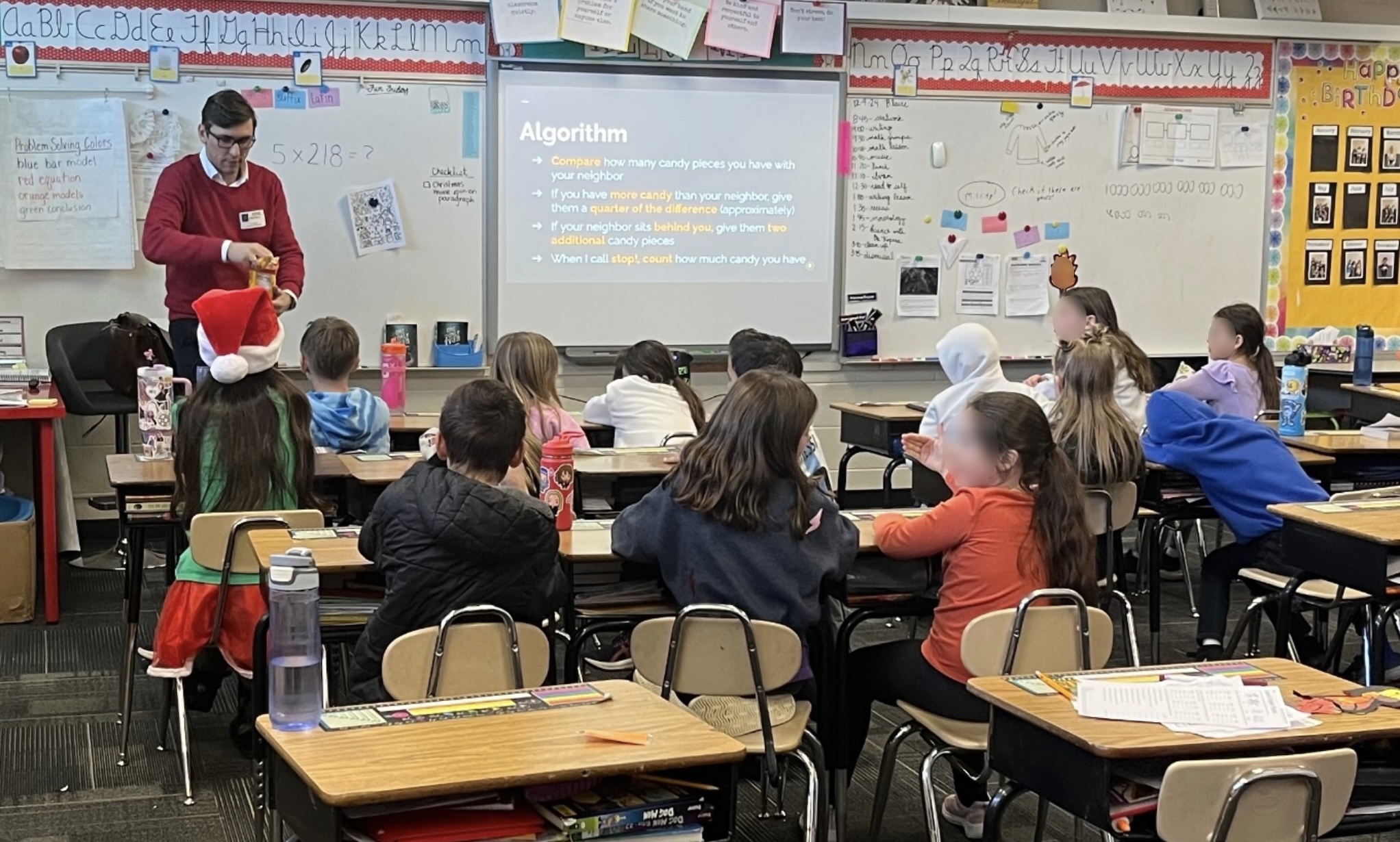

This experience was more than a technical challenge—it was an opportunity for deep reflection. How often do we, as researchers, think about who can or cannot access our work? For many of us, creating accessible content might seem like an afterthought, but this event made it clear that inclusivity is not a box to check—it’s a responsibility.

Moving forward, I see accessibility as an integral part of scientific communication. What if tactile and auditory tools became standard in classrooms and conferences? How might science advance if a broader spectrum of people, with diverse ways of perceiving the world, could contribute to the conversation?

While Amelia and I took small steps with 3D printing and sonification, the potential for these methods is vast. With technology advancing at breakneck speed, the tools to create inclusive research environments are within our reach. The question is whether we’ll seize the opportunity.